Dysphagia (trouble swallowing) can be caused by many different problems. A strictured or narrowed esophagus is one common cause, and is often related to excess acid exposure in the esophagus. Usually strictures happen at one discrete location in the esophagus (often the lower part closest to the stomach where acid reflux damage is the most pronounced).

In some patients, severe acid reflux disease can affect the entire esophagus. The treatment of choice for this is to start a proton pump inhibitor drug. After all the inflammation and ulceration caused by the stomach acid heals, fibrosis (scar tissue formation) can result in narrowing of the esophagus in multiple places. So in patients who have had severe acid reflux issues, and now are complaining of dysphagia, it is a good idea to investigate the esophagus for the presence of strictures.

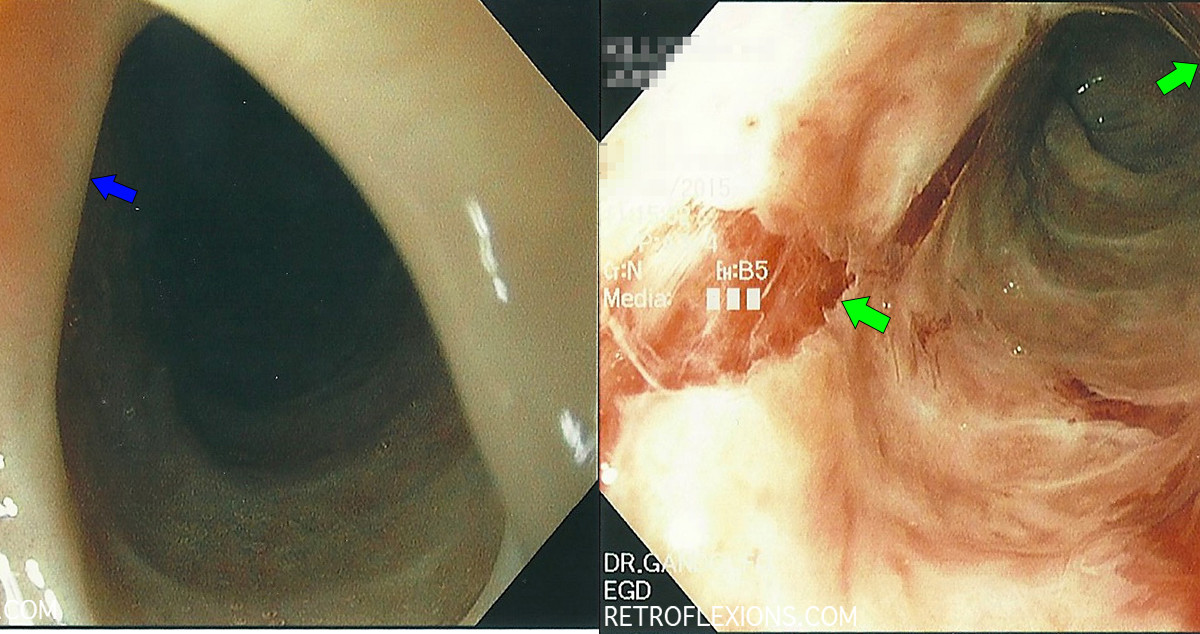

(L): Stricture (blue arrow) just above GE junction (red arrow); (R): Same stricture after dilation showing mucosal tears (between green arrows).

Here is a stricture just above the gastroesophageal junction (GE junction). It was dilated using a through-the-scope (TTS) balloon, which is basically a balloon that is inserted through the instrument channel of the scope and then can be inflated to various sizes. The balloon will stretch anything in its path to the size you select.

Dilation is best done gradually, usually in multiple endoscopy sessions, since it is safer to stretch something from 8-9-10 millimeters, then wait for some healing, then from 10-11-12 mm, and wait for some healing, then repeat until we get somewhere around 18-20 mm where there are no more symptoms of dysphagia. This is opposed to just stretching from 8-20 mm in one session where there is a higher change of perforation due to over-stretching and tearing the wall of the esophagus.

However, by definition, dilation of an esophageal stricture only happens when we produce slight tearing of the inner lining of the esophagus (the mucosa). We are actually trying to create a controlled tear in the scar tissue and therefore disrupt the stricture. So seeing some blood is actually a marker of a successful dilation.

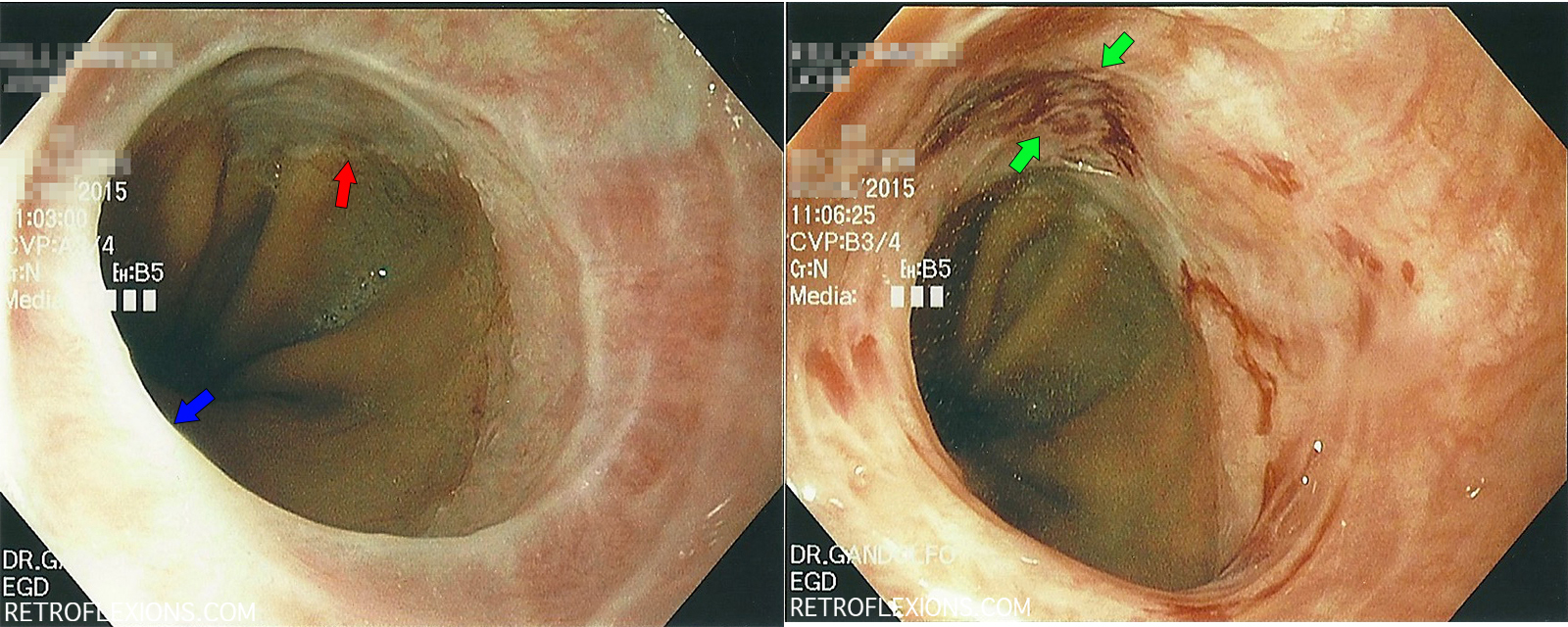

(L): tight stricture (blue arrow) would not let the scope pass; (R): after dilation multiple large mucosal tears are seen (green arrows). Bleeding is self-limited and minor.

Above is a dramatic example of multiple mucosal tears after a successful dilation. Of note, the balloon that was 1-mm smaller than the one that produced the above image actually did not dilate the esophagus at all. It goes to show that careful balloon selection and patience is the key to avoiding complications in esophageal dilation. This patient had a very fibrotic esophageal lining, and this was the stopping point in dilation that day. Also of note, his original mechanism of injury was severe reflux while critically ill with an unrelated illness (and he did not have eosinophilic esophagitis). The patient reported immediate relief of dysphagia after this procedure.

If you enjoyed this article, sign up for our free newsletter and never miss a post!