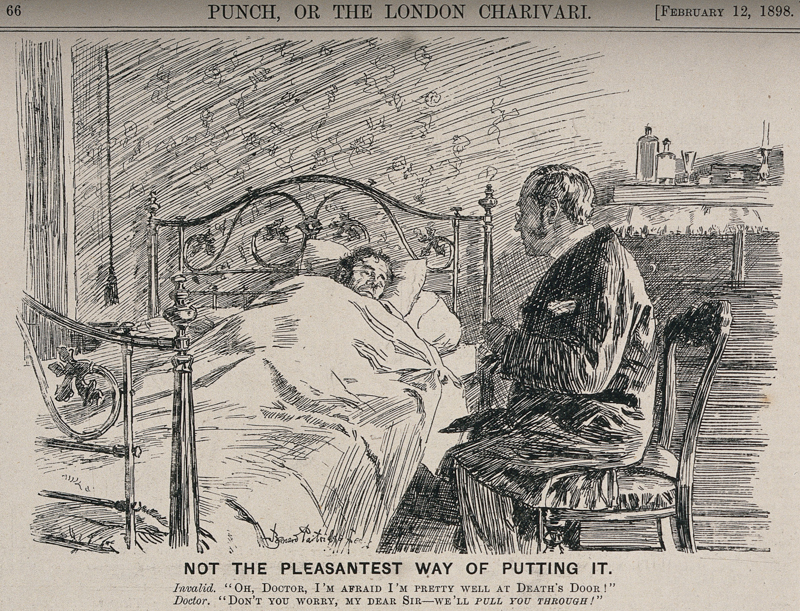

Bad news is always hard to break. I would like to think that I get better at breaking bad news after doing it over and over, but it doesn’t make it easier. Some experiences stick with you and this is one of them:

Several years ago I was making rounds in the hospital and my next patient was an almost ninety year old man who was admitted several days earlier with progressive weight loss and abdominal pain. A CT scan done on admission showed a large mass in the pancreas with innumerable metastases in the liver–an incurable disease. A biopsy of one of the lesions was already done two days earlier, and we were waiting for results. In the meantime, the patient was not eating or drinking well, and was basically bed bound. This is what is called a “poor functional status” meaning that the patient is already quite debilitated from his advanced disease and will likely do poorly with aggressive treatment such as chemotherapy.

Just before seeing the patient, who I had never met before, I discovered that the biopsy results just came back and confirmed what all the other doctors suspected. Adenocarcinoma is what the report read (bad results are always printed in bold.) I introduced myself and began talking to the patient, who was alone and still unaware of the formal diagnosis. He seemed up-to-date on what was happening to him, and knew that he had “spots” throughout his liver and pancreas. “Did those results come back yet?” he asked. I told him that the biopsy results just came in this morning, and asked him if he wanted them now. He said “yes, tell me.”

After a long explanation which basically boiled down to the word “cancer” and after staying to answer his new questions and concerns, I called his primary doctor to relay the news. “Did you tell him?” the primary doctor asked, almost accusingly.

“Of course I told him…he wanted to know,” I said. I was confused why she asked me that way, and a little put-off that she thought I was going to shirk my painful responsibility of being the first to break the bad news. Wasn’t it his right to know what was going on with his body? Besides, I thought to myself, wasn’t it somewhat obvious by looking at the scan that we were dealing with something bad? Even if we took the word cancer out of the equation, an elderly man losing weight with months of abdominal pain and something growing where it isn’t supposed to is usually a bad sign.

In my head I wondered how she explained the recommendation to do a biopsy to the patient in the first place? Did she tell him what the possibilities were? I know that I always mention that we may find something “bad” if I am sending a patient for a biopsy and I expect to find something serious. Did she mention that the spots in the liver were metastases? Did she allude to the fact that once a cancer such as this is metastatic the goals of treatment no longer include the word “cure?”

Another phone call about 20 minutes later filled in all the blanks. It was the patient’s daughter calling me, distraught and irate. Still at home and preparing to come in to the hospital, she chastised me for “telling dad what he has! How dare you! Is this what they’re teaching in medical schools these days?” The patient’s daughter soon stated that she wanted to be the one to tell him the bad news herself. I tried to explain the situation, that I was unaware of these prior plans and that the patient had told me himself that he was ready for the news. In fact, I thought he took it quite well. At that time it didn’t matter anymore, the cat was out of the bag, and all I could do was apologize. I felt awful for adding this headache to her already very bad day. I am sorry I told your dad without you being there; I am sorry he has terminal cancer; I am sorry for causing you grief; I am sorry for everything.

Nowhere in the state-of-the-art electronic medical record was this most important fact found. No red box popped up making me click “acknowledge” that the patient is to be shielded from his diagnosis. Notes from his other doctors did not warn me. How could I have known? Even if I did know, is it right to hide the diagnosis from the patient, who is mentally competent and asking me to tell him? Is my duty to the patient or his family?

Perhaps it would have been best to do some reconnaissance first, asking the primary doctor, the nurse, and the patient who are the key players in the family, and who should be present for any serious conversations. The risk is that a white lie would need to be told to the patient who inevitably will ask “did you get the results yet?” before the family has arrived.

Let me go and check, I will let you know if they are back…

If you enjoyed this article, sign up for our free newsletter and never miss a post!

Image via Wellcome Images