Diverticulosis is the most common cause of significant lower gastrointestinal bleeding. The appearance of diverticulosis on colonoscopy is that of small outpouchings, or pockets, in the colon wall. When severe, the colon can have a “swiss cheese” appearance, due to the many pockets present.

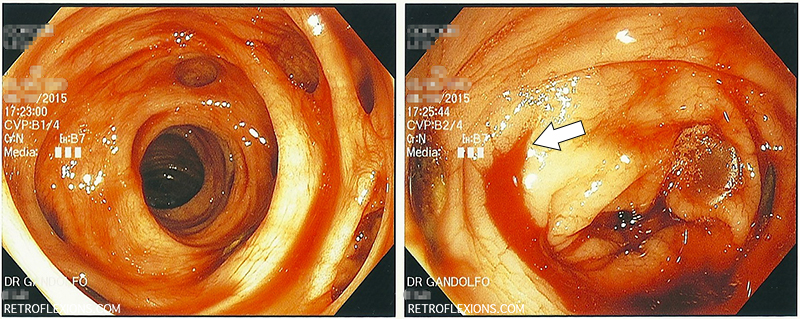

(L) Multiple sigmoid colon diverticuli and obvious blood in the colon; (R) The white arrow shows the actively bleeding diverticulum near the hepatic flexure.

Diverticular bleeding can happen without warning, and is painless. A large volume of bright red or sometimes dark red blood per rectum is often the only symptom. In most patients who are not on blood thinners, diverticular bleeding eventually stops by itself. However, this may take a day or two and require multiple blood transfusions to support the patient while he or she is losing blood rapidly. This can make treating diverticular bleeding frustrating since often in the time it takes for the patient to present to the hospital, get stabilized, transfused, and prepped for a colonoscopy the bleeding has already stopped and no clear source is found.

Nevertheless, there are many ways to treat presumed diverticular bleeding, and colonoscopy is often employed as both a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure. The added advantage of colonoscopy is that other pathology can be detected in the case of non-diverticular bleeding. Bowel prep is still important when looking for a bleeding source on colonoscopy, however in the presence of active bleeding it is near-impossible to get a good bowel prep due to the ongoing bleeding. If the bleeding is rapid enough, the blood itself can act as a bowel prep and flush out any stool that remains in the colon (distal to the bleeding site). If the patient is otherwise stable at the moment, sometimes a tap water enema is all that is needed to make the prep adequate to do an urgent (same day) colonoscopy.

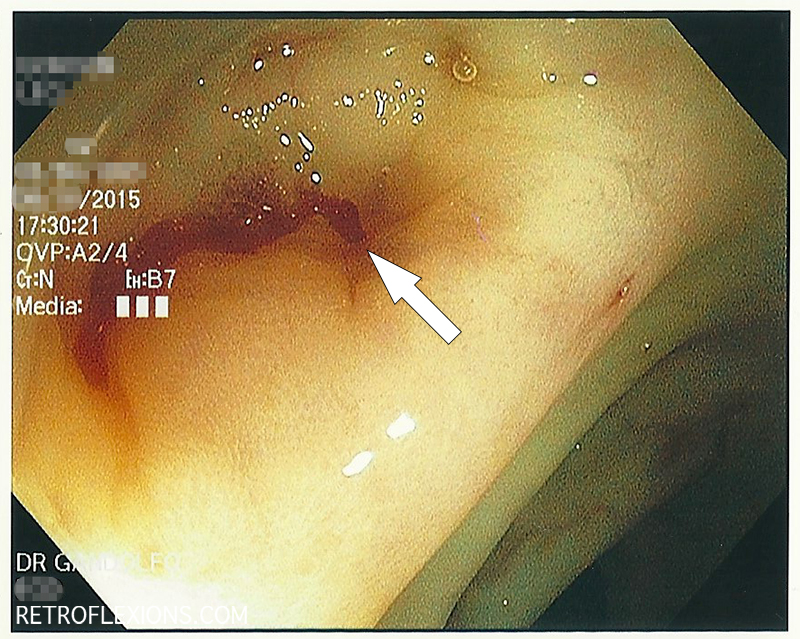

After injection of epinephrine into the bleeding diverticulum. The bleeding is slowed to a trickle and the bleeding site is identified (white arrow).

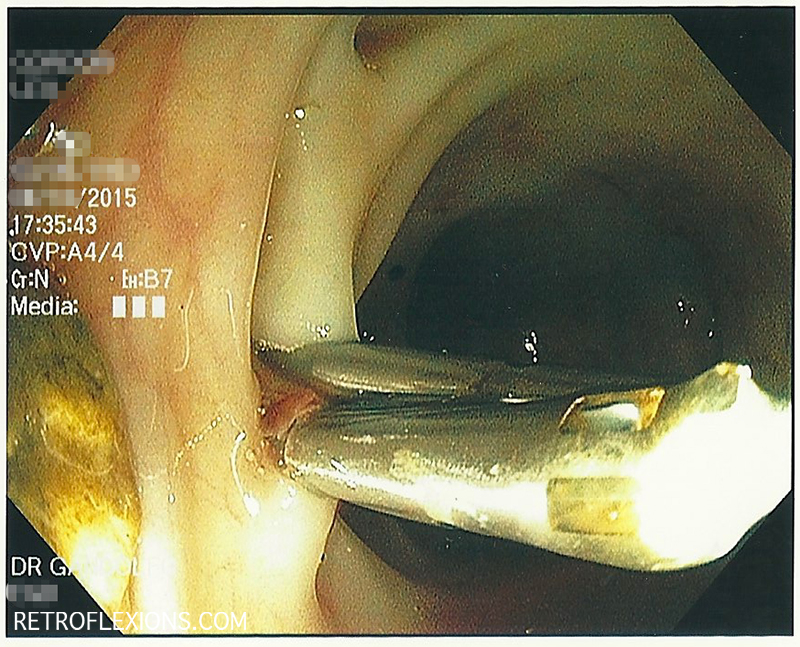

In the pictures above, the bleeding diverticulum was found and epinephrine was injected to slow the bleeding enough to see exactly where it was coming from. There is a small artery associated with each diverticulum, and if the artery ruptures (for various reasons), bleeding occurs. To best treat the bleeding, it is important to see exactly where the artery is located.

The bleeding artery is successfully treated with clips. These clips will eventually fall off in a matter of weeks, and by that time the body will have healed the bleeding site. Despite effective treatment of an episode of diverticular bleeding, it is important to remember that most patients have multiple diverticula, and another episode of bleeding can happen at any time from a separate diverticulum.

The issue of when to perform colonoscopy on patient with significant lower gastrointestinal bleeding has been studied in the past. Several studies show that “urgent” colonoscopy (done no later than 8-12 hours from presentation to the hospital) found more actively bleeding (and therefore treatable) lesions. What is interesting however is that when compared to “elective” colonoscopy (done within 2 days of presentation to the hospital), urgent colonoscopy did not improve the important endpoints that matter, namely mortality, rebleeding rate, hospital length of stay, or units of blood transfused.

Therefore, done within a bleeding protocol consisting of ruling out upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and performing appropriate radiologic tests, elective colonoscopy and urgent colonoscopy seem to be equivocal. However, as with anything, these approaches must be tailored to the individual patient, the competing comorbidities (such as need to resume blood thinners), the time of day, and the local expertise available.

If you enjoyed this article, sign up for our free newsletter and never miss a post!

References:

Green BT, Rockey DC, Portwood G, et al. Urgent colonoscopy for evaluation and management of acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:2395-2402.

Laine, L and Shah, A. Randomized trial of urgent vs. elective colonoscopy in patients hospitalized with lower GI bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2636-41.