Knowing your limits is a very important part of doctoring. As Mark Twain said, “Good decisions come from experience. Experience comes from making bad decisions.” Tackling big polyps with the scope is no exception to this rule. Although techniques for removing large polyps have evolved over the years, and maneuvers that were once deemed “high-risk” are now being taught fairly routinely to junior GI fellows, there is still an individual comfort level that practitioners should identify in themselves and respect.

Most practicing gastroenterologists have a certain size criteria for polyps that they will not attempt to remove: When these lesions are found the decision will be to refer the patient to another doctor to remove the lesion endoscopically, or to refer to a surgeon to remove the polyp surgically. But what exactly should you do when encountering a polyp that is beyond your comfort level?

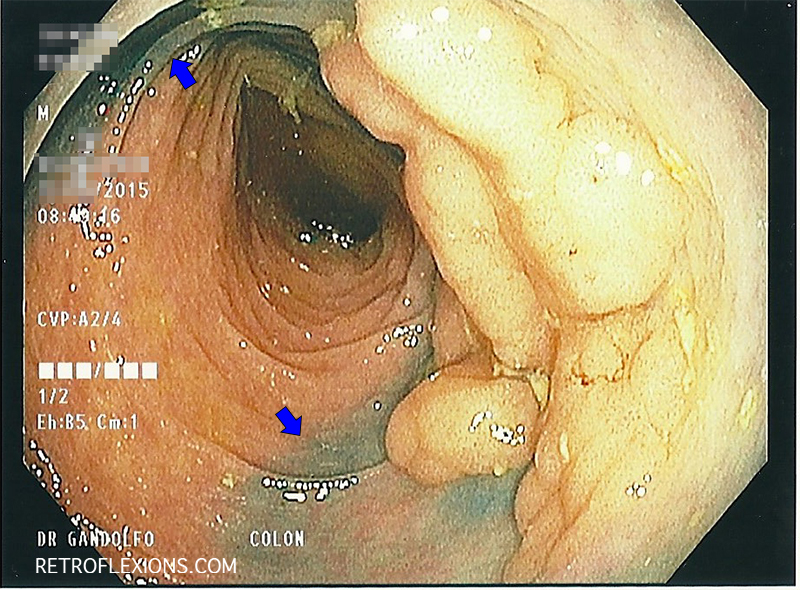

Large polyp in transverse colon. Blue arrows denote tattoo marks left by referring doctor. Note that the tattoo mark extends to the edge of the polyp (and below the polyp).

Usually the best thing to do is to just leave the polyp alone. If there is any question about cancer being present in the lesion, then a cold forceps biopsy can be taken. Take care to biopsy a bulky part of the polyp, and try not to biopsy too deeply. Deep biopsies can cause some fibrosis to occur when healing, and this can tether the polyp down to the submucosa, making later resection more difficult.

If leaving a tattoo is necessary, such as in a flat lesion that may be hard to find later, please take care to leave the tattoo several folds away and separate from the polyp itself. Document in your report where the tattoo is in relation to the lesion. Don’t tattoo directly into, under, or next to the polyp itself. This can cause scar tissue to form in the submucosa and makes future resection more difficult than it needs to be (as in the large polyp shown here).

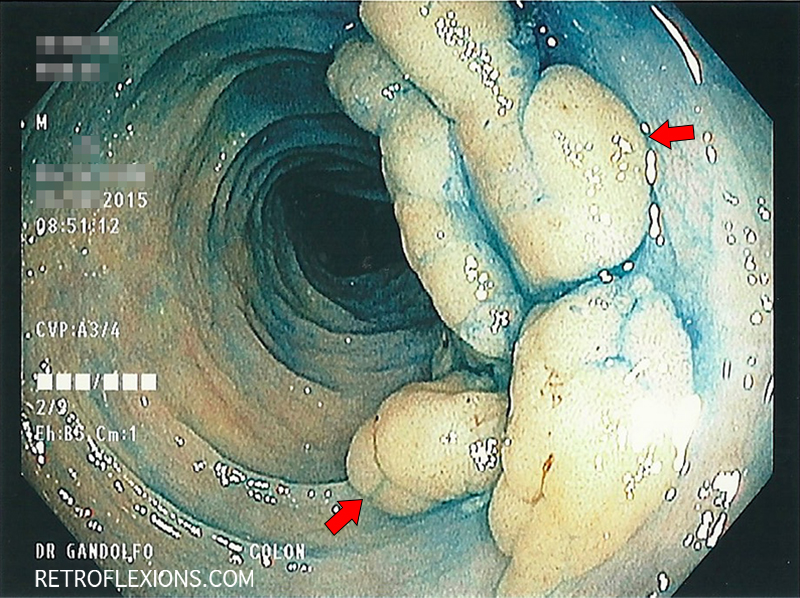

After spraying the lesion with methylene blue dye, the edges of the polyp are more apparent (red arrows show the edges of the lesion).

Some more pointers: Don’t use cautery such as argon plasma coagulation on the polyp since this may make future endoscopic resection nearly impossible for the same reasons as above. If the polyp is bleeding at the time of colonoscopy, then either resecting it right then and there or quickly referring the patient to another endoscopist who can remove the lesion is the better option. If you do start using a hot snare to resect the lesion, make every attempt to remove the entire lesion since future resection will be more difficult due to scarring.

Do refer these patients to a practitioner skilled in endoscopic mucosal resection. It is almost always safer and less invasive overall to remove most colon polyps endoscopically, and most patients can avoid the need for surgery.

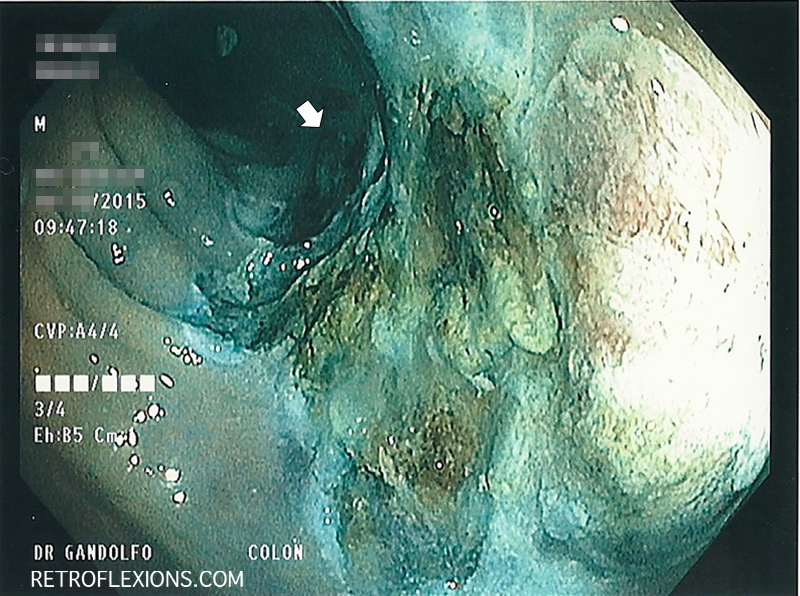

The appearance of the site after removal of the polyp. The white arrow shows the proximal-most edge of the resection. Pathology revealed a tubular adenoma.

If you enjoyed this article, sign up for our free newsletter and never miss a post!